It is a crisp summer evening in Alpine Victoria. Across the vista, the dusk clouds roll in, changing the light from a gentle mauve into a rich dark blue. Soon nightfall will turn the clouds into a shapeless darkness upon the horizon, but for now each one is trimmed with a brilliant glow, as though they have been delicately edged by a heavenly seamstress. For one passing moment the world is still.

As I recall this scene, I am immediately struck by the dull inadequacy of language to describe such majesty. How could any representation, be it literary or painterly, capture the profound, haptic experience of being in nature? How could a painting evoke the encompassing awe that causes one to swoon in the face of the sublime?

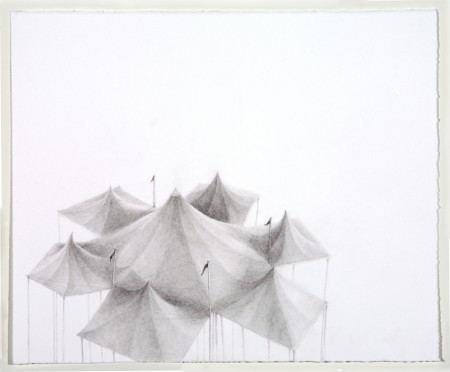

Over the past fifteen years, Kirrily Hammond has explored many different landscapes in her paintings, prints and drawings. Her early works revelled in a fantasy world of the imagination, in which anamorphic trees jostled with ethereal spirits and circus ghouls. More recently, however, she has found her inspiration in the real world, taking the landscapes of Gippsland, Mount Buller and Japan as her subject. In doing so, she has pushed away from the enclosed, personal world of the subconscious, towards a much more universal experience. For as much as we have shared dreams and fantasies, the surrealist vision is a highly personalised one. In her most recent landscapes, Hammond has gravitated towards intentionally unspecific or generic settings. Her paintings, she stresses, “are not about the landscape” and she intentionally seeks scenes that are geographically unrecognisable. In Hammond’s paintings, the landscape is clouded with the hazy light of dusk or dawn, and seems to exist as little more than a prop for her experiments in light and texture. As such, they take on the uncanny possibility that they could be anywhere. Although impossible to pin down their precise location, each one has a striking sense of familiarity, as though it is a place that one has visited in the distant past.

Concurrent with this thematic development, Hammond has settled into a small format that perfectly suits her cause. Each work exists as an exquisitely sealed hermetic portal onto a distant, but disquietingly familiar world. Looking at her paintings of clouds, such as Flight JQ3 2009, it is impossible not to be reminded of the tiny cabin windows of commercial airliners, while in her Gippsland Twilight series, the format evokes the view from a speeding car window, or perhaps that of a blurry Polaroid snap-shot.

In these paintings, Hammond is asking how we frame the sublime. Not simply how we represent the majesty of nature, but also how we recall it, how we package it, and how we consume it. More pertinently, they question how we overlook this majesty in our everyday lives. In the safe, comfortable space of the aeroplane or automobile, how often do we fail to notice the sublime as we speed on by? Margaret Morse has termed this the ‘precondition of distraction.’ The car interior becomes a de-realised ‘non-space’ in which the traveller is insulated from the outside world, achieving what Morse calls a ‘mobile privatisation’ that displaces us from our surroundings. A similar sense of ‘distraction’ might be conjured by the image of the tourist, unable to quantify any experiences not captured through the prism of their camera.

This is the challenge set by Hammond’s paintings, prints and drawings. For they are not about replicating the sublime, or even using paint to imitate nature in order to create a virtual swoon. Rather, Hammond’s vision is driven by a much more profound romanticism. As her paintings have become less reliant upon fantasy, they have insistently drawn attention to the beauty inherent in the world around us. Rather than being portals to an imaginary world, they point to a world just outside our windows; rather than a mystery beyond reality, these works point to the mystery within reality. It is this sentiment that causes one’s heart to swoon before Hammond’s paintings. As Sasha Grishin notes, “In Hammond’s depiction of the sublime, we do not experience the quality of terror and awe, but a sense of glowing inner radiance.” This is not the classical sense of the sublime, for there is no fear in this world. The mystery of Hammond’s work comes from seeing the familiar as anew; realising beauty where before there was only the ordinary; finding majesty in the mundane; grandeur in the generic; the sublime in our everyday lives. Hammond challenges us to be constantly aware of the wonder and beauty that surrounds us, and that through this mystery we might learn to swoon again.

Henry F. Skerritt

Download essay by Henry F. Skerritt